Is lactose intolerance as common as you think? What it is, how to test + my lactose intolerance results

I’ve written quite a lot about food intolerance since I’ve suffered with a lot of digestive issues myself and needed to control them to optimise my own health. While I gave an overview of types of food intolerance in this guide, I’ve not covered lactose intolerance specifically.

A lot of people seem to report lactose intolerance, but it actually seems to be commonly misunderstood. Did you know, for example, that lactose intolerance is thought to affect only around 5-16% of people in the UK? A far lower number than I often see being thrown around on social media.

Because of these kinds of misunderstandings, a lot of people self-diagnose or follow overly-restrictive diets.

There was a point in time where I suspected that I had issues digesting milk. I didn’t know if it was due to a milk protein, lactose, or perhaps something else in my diet entirely, that I happened to consume at the same time.

While I have tried to reduce my cow’s milk intake for sustainability reasons anyway, I felt it was important, from a health perspective, to better understand what could be negatively affecting my body. So, I took a lactose intolerance test.

This article draws from my own experience as well as research into exactly what lactose intolerance is, why the rates vary among different populations around the world, and how you can test to see if you actually have it.

But before we get started, here’s a fun fact: when I was younger, I thought that ‘lactose intolerance’ was ‘like toast and tolerance’ and was some kind of idiom that I didn’t properly understand yet.

Thankfully, I understand it now. So here we go.

What is lactose intolerance?

Lactose intolerance is the inability of your body to digest lactose, which is the naturally-occurring sugar in milk.

Your body requires the enzyme lactase, produced in your small intestine, to break down lactose into glucose and galactose, to then be properly absorbed.

However, for various reasons, in some people, the lactase enzyme isn’t there to do the job.

What are the symptoms of lactose intolerance and why do these occur?

Symptoms of lactose intolerance include:

- Gasiness

- Bloating

- Stomach pain

- Diarrhoea

- Stomach rumbling

These are all fairly unsurprising symptoms of digestive issues that most of us could identify. But I never knew exactly why these issues occurred until I did a bit of further research…

These symptoms pretty much all arise from the large amounts of gases and fatty acids that are created when undigested lactose ferments and becomes food for your gut bacteria.

The large amount of carbon dioxide that is produced can be eliminated through your large intestine… (You know what I mean).

But other gases like hydrogen and methane are typically transported through the wall of the small intestine, into your blood, and are eventually expelled by your lungs. This can be uncomfortable and may also cause bad breath.

Meanwhile, the fatty acids that are produced by your gut microbes can draw water into the intestine. This is why you may experience gurgling sounds caused by intestinal movement, and a dilution of your intestine’s contents that leads to diarrhoea.

Other symptoms, although less common, might include:

- Heartburn

- Nausea

- Fatigue

- Migraines

What are the different types of lactose intolerance?

While you were probably already familiar with the concept of lactose intolerance, what is less well-known, especially by anyone who hasn’t been formally diagnosed, is that there are different types of lactose intolerance:

Primary lactase deficiency

Primary lactase deficiency is the kind of lactose intolerance that people most-often refer to as it’s the most common cause of lactose intolerance worldwide.

Lactase deficiency, in this case, is caused by declining activity of the LCT gene, which provides our body with instructions for making lactase.

In a lot of people, the expression of this gene declines after childhood, since once we have finished breast-feeding, we don’t rely so heavily on milk for survival. This could happen at any age between weaning and becoming a pensioner.

This type of lactose intolerance is also known as lactase non-persistence, since your body’s ability to produce lactase does not persist throughout your lifetime.

Because this type of lactose intolerance has a genetic component, the prevalence of it varies hugely across the world. This is why some sources state that 65 - 75% of the population suffer from lactose intolerance, when in fact, on some continents this is much higher, and in areas like Northern Europe, much lower at around 5%.

Here’s how genetic testing company, DNAFit, describe the differences in Europe:

A few thousand years ago a genetic mutation appeared in central Europe in the lactase gene, which meant that the gene stayed active all through life – creating lactose persistence. After a few generations it became a common and selected for mutation, as dairy became an increasingly important part of central European life.

Some other sources suggest that the gene mutation came about due to the introduction of dairy farming in this part of the world approximately 10,000 years ago.

This diagram from DNA testing company FitnessGenes is also useful to show how the genotypes and occurrence of lactose intolerance varies globally.

Note: changes in your body’s production of the lactase enzyme based on the LCT gene is a great example of ‘gene regulation’ – the process by which genes can be turned on or off throughout your life, depending on a variety of factors.

Secondary lactase deficiency

Secondary lactase deficiency is a side-effect of (is secondary to…) another condition. People with coeliac disease or inflammatory bowel diseases may experience lactase deficiency due to damage to the small intestine mucous membrane.

Drug use (including antibiotics and chemotherapy), stomach bugs like gastroenteritis, surgery or an imbalance of bacteria in your gut can also cause disruption to lactase production.

The good news is that in these cases, lactose intolerance is likely a temporary condition that will resolve when normal function of your intestines resumes.

Because I have cystic fibrosis, I had wondered whether I could be affected by secondary lactase deficiency, since people with CF already have digestive issues due to abnormal intestinal mucosa.

How to test for lactose intolerance

There are few tests for lactose intolerance, some of them more complex and invasive that others.

Since I’ve already mentioned that there’s a genetic component to some types of lactose intolerance, let’s start there.

Genetic testing for lactose intolerance

Certain genetic tests may indicate whether you carry a gene that is linked to lactose intolerance.

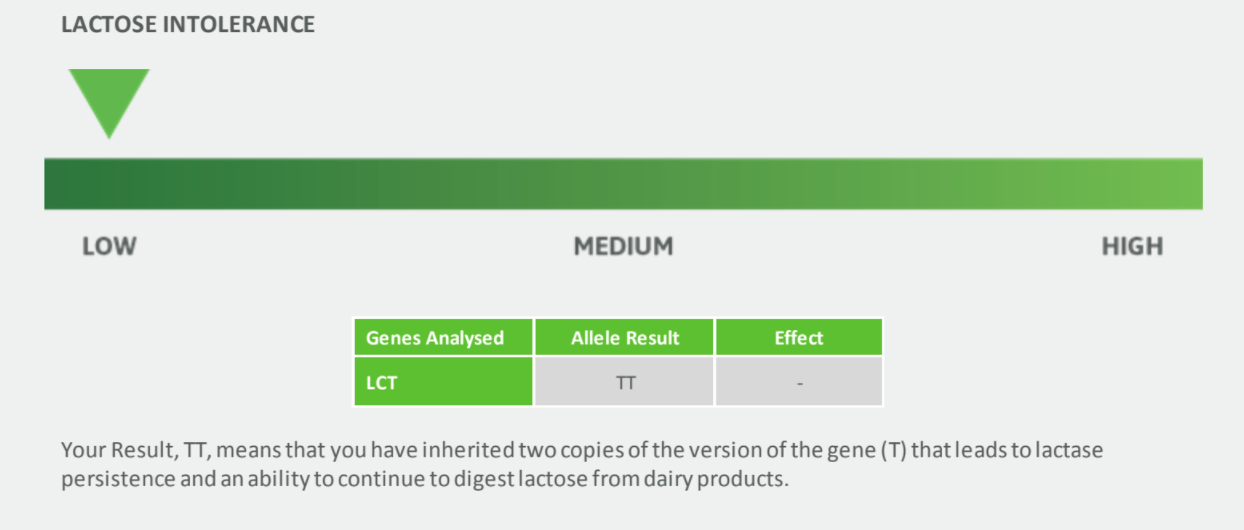

I took DNA tests with DNAFit and FitnessGenes a couple of years ago, which both looked at the LCT gene. They both concluded that I have two copies of the 'lactose tolerant' T allele and, since I am genetically lactose tolerant, I will likely be able to continue digesting lactose.

There are a few of problems with genetic testing for lactose intolerance, however:

- They ignore factors that contribute to secondary lactase deficiency

- If you have a genetic predisposition to lactose intolerance, they can’t tell you if you have developed this yet. Some people don’t present symptoms until they are much older than others

- These tests can’t cover all the genetic mutations linked with lactose intolerance that exist within different populations across the world

However, there are a number of tests that can determine whether you are currently suffering from lactose intolerance…

Lactose elimination

Perhaps the simplest and most cost-effective way to see if you have lactose intolerance is to eliminate lactose from your diet for a couple of weeks before reintroducing and monitoring symptoms.

An elimination diet is fairly standard practise when trying to identify food intolerances. However, given that there are other components in milk that people don’t tolerate well, you may prefer to pick a testing method that is a little more specific...

Intestinal biopsy test for lactose intolerance

As with other types of digestive issue including coeliac disease, the ‘gold standard’ test for lactose malabsorption relies on an intestinal biopsy.

It’s super invasive and so not widely used. It tends to only be used as a last resort for people who have more severe cases that need deep investigation.

Urinary galactose test for lactose intolerance

I already mentioned how lactose is a disaccharide (made up of two sugars) and that one of the sugars that lactose is broken down into is galactose.

So, one way to test whether the body is effectively digesting lactose, is to measure the levels of galactose that are present. This can be detected in a urinary test.

A high level of lactose suggests it is not being properly broken down. Higher levels of galactose, suggests that it is.

Breath test for lactose intolerance

Much more commonly, people will take a breath test. It’s non-invasive and pretty straightforward but will involve you consuming a decent amount of pure lactose in order to cause your body to react in a way that can be tested.

So, if you really are lactose intolerant, it won’t be all that enjoyable for you...

Given that lactose intolerance mainly causes tummy troubles, you may be wondering how a breath test is useful?

Well, the undigested lactose in your small intestines ferments, producing gases like hydrogen and methane, which are absorbed into the bloodstream and eliminated via the lungs when you exhale. So by capturing your exhaled breath and measuring the concentration of those gases, it’s possible to determine lactose intolerance.

Clever, hey?

The downsides? Not many, which is why it has become so widely used.

Although one journal article that I read explained that, “a false-negative result can occur if antibiotics have been taken within one month of being tested, if colonic pH is acidic enough to inhibit bacterial activity, or if there has been adaptation in the bacterial flora as a result of continuous lactose exposure".

But generally, breath tests for lactose intolerance are regarded pretty highly. It was the method that my dietician suggested I explore if I ever wanted a solid confirmation. And that’s why I decided to take one myself.

Cerascreen Lactose Intolerance Test Review

Cerascreen are a German company that I first came across at the annual Allergy and Free-From Show at London Olympia earlier this year. I was fascinated by their wide range of tests (some of which I’ll be telling you more about shortly!) and, having had a history of issues with milk products, I decided to take their Lactose Intolerance Test to (hopefully!) rule out lactose digestion issues.

Like other intolerance tests I’ve done before, the test kit arrived in a neat box containing the testing kit:

- 50g of lactose (powdered)

- Mouthpiece for air sampling

- 5 air test tubes

- 5 colour-coded labels for the test tubes

- Return envelope (to send your test off to the lab)

- Your activation card, with your unique code for redeeming your results

The test itself is pretty straightforward, if not a little inconvenient. You take a sample of air to start with. Then, you drink the lactose. After that, you take 4 more samples at 30 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours and 3 hours after ingesting the lactose.

See? Straightforward. But inconvenient. Especially if you experience severe symptoms when consuming lactose, you might want to take a day off work to do this test to avoid discomfort and to ensure that you collect samples at the correct intervals.

Working from home, I found the test manageable. I thoroughly read the instructions and set the test up. I mixed up and drank the lactose solution (which looked, smelled and tasted like I’d mixed icing sugar into water. Not surprising though given that lactose is a sugar). And then I set alarms on my phone to go off at the required intervals. Once complete, I popped it in the jiffy bag with a freepost label and sent it off to the lab.

The test is simple, but I wish I’d have had a heads up on a few things before getting started. So, here are my words of warning:

1. Only take this test on a Monday or Tuesday

The leaflet within the pack states that you should ’only take the sample between Monday and Tuesday and send it on the same day it was taken’. This ensures that their lab receives and processes samples before a weekend. It makes sense, but it’s definitely something that you should know in advance and plan for, rather than find out when you open the pack ready to take the test.

2. Do not consume food or drink containing lactose on the day of your test

Probably if you suspect that you have a lactose intolerance, you won’t do this anyway, but this is important in order to get an accurate test. In fact, a lot of sources suggest that you should do the test in the morning, fasted. You can still drink water and take medications.

Based on other guidelines, you might want to avoid doing the test within two weeks of having oral antibiotics, since this could disrupt your gut microbes. Likewise, avoid taking the test in the couple of weeks after a colonoscopy and for a few days after taking any laxative medications. Eating very high fibre the day before your test could also influence the results.

3. The test kit contains a needle. You don’t need to expose it

There is a needle in the mouthpiece device which pierces the top of the test tube to collect your air sample. I did not realise at first that this was covered with a fine rubber sheath. But when I did, I panicked that I hadn’t removed it and (wrongly) assumed that the three samples that I had already collected were void. So I didn’t send them off and had to retake the entire test.

You see, there are warnings everywhere about the test containing a sharp needle, and all of the diagrams show a needle, so when I realised it wasn’t actually exposed, I thought I must’ve done something wrong.

In fact, when pressed into the collection tube, the needle also pierces the rubbery sheath that covers it (though you can't see this when taking the sample), so I had no need to worry, but since there’s a chance that anyone else taking this test could second guess themselves too, I thought I’d better make that point clear to avoid any other tests being wasted…

The test costs £59.99 and is available through Cerascreen (where you can use my code 'NATALIE10' to get 10% off) or through amazon, where it is eligible for amazon prime.

My Lactose Intolerance Test Results

I received my lactose intolerance test results one week after posting the test tubes. They are available in a pdf report format from the ‘My Cerascreen’ area of the website.

My results? No lactose intolerance is suspected.

Given my DNA results and the fact that I felt totally fine after downing a pint full of sickly-sweet lactose, I guessed that this would be the case. Glad I was right!

Reminder: there are other types of dairy intolerance

Convinced you have an issue with milk digestion, but you've ruled out lactose intolerance with a negative test result? Well, there are lots of different compounds that make up milk besides lactose, meaning that they are different types of dairy intolerance.

I’ve talked before about dairy intolerance and the A2 protein in milk so go and check out that article if you haven’t already. That’ll bring you right up to speed.

Essentially, while lactose is a milk sugar, there are also milk proteins that can cause similar symptoms of intolerance. You will have likely heard of whey protein, from milk. But another major protein component of milk is casein (something you may be familiar with as a slower-digesting milk protein often sold by supplement companies).

However, depending on the genetics of the cow producing the milk, there are slight variations in the type of beta-casein found in the milk you are drinking. One type is A1 and one is A2. I go into more depth on this in my original article on dairy intolerance and the A2 milk protein, so take a read and see if that may be another avenue worth you exploring.

So what next for me?

With the combination of my genetic results, hydrogen breath test results and from monitoring my own symptoms after downing 50g of lactose, I’m pretty sure that I’m not lactose intolerant. Right now.

While, based on my genetic results, I know that I’m unlikely to develop primary lactase deficiency, I have to always consider that with a condition affecting my digestive system in many ways, there is a chance that I could experience secondary lactase deficiency at some point in my life.

Cystic fibrosis affects the whole body, including the digestive system, in many ways. I have to take digestive enzymes every time I eat, daily medication for acid reflux and have to be extra conscious of my fluid and fibre intakes. The medication that I have to take, including occasional strong antibiotics, can damage the digestive system further.

There’s not a lot of research into CF and lactose intolerance, but now that I’ve learnt more about it, and know that my risk of digestive issues may be higher at certain times (later in life, when on antibiotics), I can look out for symptoms of lactose intolerance and adjust my diet accordingly.

If you want to learn more about lactose intolerance, I’ve popped some links below. And remember, you can get this test through Cerascreen, where you can use my code 'NATALIE10' to get 10% off.

If you're interested to read more on the topic, here are some of the resources that I referred to when researching and writing this article:

- https://patient.info/doctor/lactose-intolerance-pro

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/lactose-intolerance/

- https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/lactose-intolerance#diagnosis

- http://www.europeanreview.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/018-025.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3401057/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/nature15393

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11761016

The lactose intolerance test kit was provided by cerascreen for trial purposes. This article contains affiliate links.